LUCIEN PISSARRO

Paris 1863 - 1944 Hewood, Somerset

Ref: BV 212

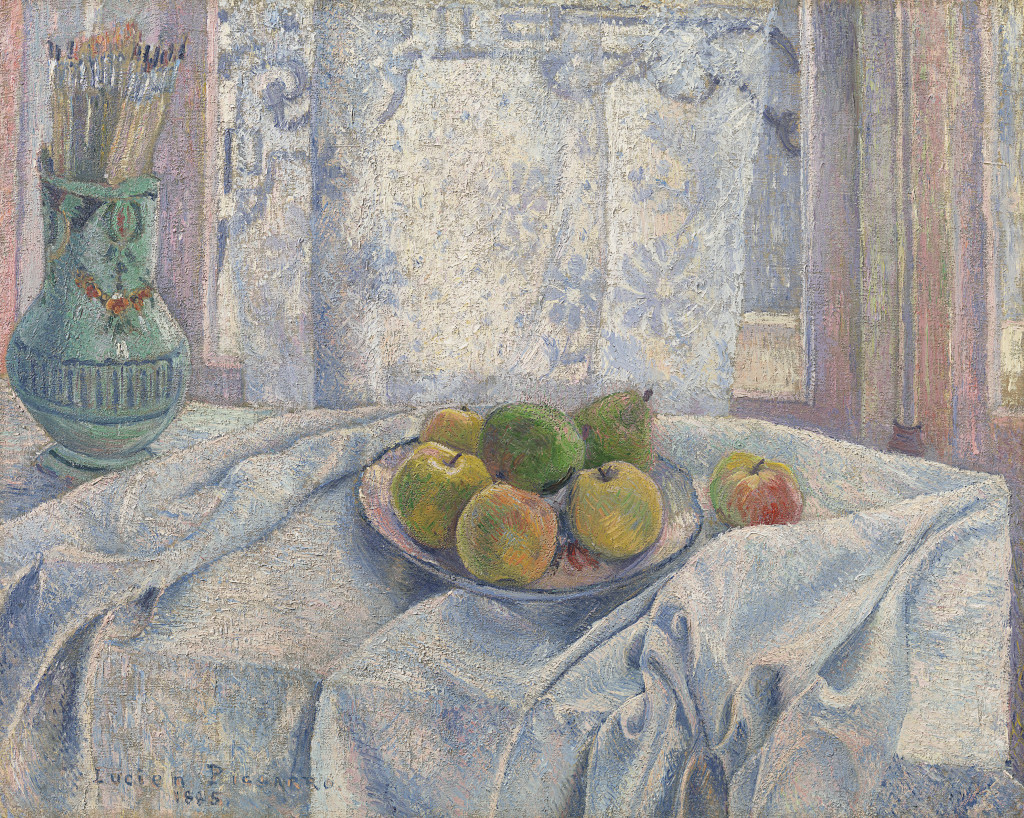

Apples on a tablecloth against a lace-curtained window

Signed lower left: Lucien Pissarro. / 1885.

Oil on canvas: 25 ¾ x 32 in / 65.4 x 81.3 cm

Frame size: 33 x 40 in / 83.8 x 101.6 cm

In its original period composition Louis XIV style gilded frame

Provenance:

The artist and by family descent until 1963;

Browse and Derby, London (as Nature morte);

by whom sold to M Herrera, South America, July 1987 (label on the reverse)

Exhibited:

Paris, Salle de la Maison Dorée, 15th May-15th June 1886, no.114 (as Nature morte)

London, Arts Council of Great Britain, Lucien Pissarro 1863-1944: a Centenary Exhibition of Paintings, Drawings and Graphic Work, 10th January-9th February 1963, no.1 (as Still life with apples, lent by Orovida Pissarro), with tour to City Art Gallery, Manchester; City Art Gallery, Bristol; City Art Gallery, Dundee; The Minories, Colchester and the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

London, Leicester Galleries, New Year Exhibition, 1964, no.89 (as Still life with apples)

Literature:

Recorded in John Bensusan-Butt’s list of paintings by Lucien Pissarro at The Brook, Stamford Brook, in 1949

Anne Thorold, A Catalogue of the Oil Paintings of Lucien Pissarro, London 1983, pp.4; 42, no.6

Joséphine Le Foll, L'Impressionisme, Paris 2020, pp.302-3, illustrated in colour

This painting, a rare still life among Lucien Pissarro’s oeuvre, is an outstanding work of his early years, showing the sophistication that he had achieved even by the age of twenty-two. Having abandoned his mother’s fond wish that he should become a businessman in London, Lucien returned to France from 1884 to 1890, studying wood-engraving with Auguste Lepère. The following year he began to work on illustrations for children’s books and magazines, which was to become the genesis of the Eragny Press, the exquisite private press that he founded upon settling permanently in England in November 1890.

Apples on a tablecloth is a manifesto of a new way of seeing. Moving between Paris, the Pissarro family home at Eragny and relatives in northern France, Lucien was in the centre of a ferment of artistic debate. In 1885, the year this still life was painted, he met Paul Signac, Georges Seurat and Théo van Rysselburghe and was enthused with their theories of Pointillism, in which compositions were built up with separate dots of vibrant colour to fuse into a picture on the retina. Camille Pissarro was equally fascinated by this experiment and at the eighth and final Impressionist Exhibition of 1886 he, Lucien, Signac and Seurat caused outrage as exponents of Pointillism: Neo-Impressionism was born.

Apples on a tablecloth slightly predates Lucien’s Pointillist paintings, but the tipped-up picture plane, with the rumpled tablecloth deployed on the surface as a decorative element, and the boldly sculptural apples show how much he was in tune with the avant-garde. The apples are built up from unmixed hatchings of pure colour, dashes of emerald green, red and yellow. They have parallels with the still lifes of Paul Cézanne, whom Camille Pissarro had championed since they had met in 1861, calling him ‘one of the most astonishing and curious temperaments of our time’[1]. Cézanne in return said of Camille ‘he was a father to me’[2]. It may be significant that Cézanne passed briefly through Paris and probably met Camille in the summer of 1885, on his way to a long sojourn in Provence.

Lucien sets himself a challenging task, basing his composition on large areas of white. The tablecloth with its myriad folds is a skein of interconnected, richly impasted coloured shadows: lilac, pink, grey, violet. The light flowing through the patterned, translucent curtain is a tour-de-force, as is the treatment of the window frame, bathed with brightness. Far to the left Lucien sets a patterned ceramic jug filled with paintbrushes. In neat, serried ranks, they look like soldiers on parade: a statement that this is a young artist to be taken seriously.

In 1886 Lucien met Vincent van Gogh, newly arrived in Paris. The following year Vincent dedicated à l’ami Lucien Pissarro his Basket of apples now in the Kröller-Muller Museum, Otterlo. With its slanting picture plane, focus on white and vigorous, sculptural brushwork, it is no doubt a homage to his friend’s Apples on a tablecloth.

Lucien Pissarro’s house, The Brook, Stamford Brook.

Vincent van Gogh, Still life with apples. Kröller-Muller Museum, Otterlo.

LUCIEN PISSARRO

Paris 1863 - 1944 Hewood, Somerset

Lucien Pissarro was the eldest son and pupil of Camille Pissarro. He grew up among the Impressionists, and frequent visitors to the family home included Monet, Cézanne and Guillaumin. Although he attempted a career in business, he quickly abandoned it and after spending the year 1883 studying in England, which he had already visited with his family during the Franco-Prussian war in 1870, he returned to Eragny and studied wood-engraving under August Lepère.

In 1885, both Camille and Lucien were introduced to Georges Seurat and his disciple Signac in Paris, and both were drawn towards Neo-Impressionism. All four artists’ work was shown together in a separate room at the eighth and last Impressionist show in 1886 (Lucien Pissarro's entry consisted of woodcuts and watercolours). Pissarro exhibited with the Salon des Indépendants between 1886 and 1894. During this period he experimented with Divisionism; however, he continued to produce woodcut illustrations, prints and lithographs, which formed the major part of his work until 1900.

By then he was living permanently in England and he married a British woman, Esther Bensusan (1870-1951), with whom he formed the Eragny Press which produced thirty books before it was forced to close with the onset of the Great War. Pissarro, who had begun painting again after the turn of the century, began exhibiting with the New English Art Club in 1904, joined the Fitzroy Street Group in 1913 and the Monarro Group in 1919. Lucien Pissarro promoted Impressionist theories to artists such as Sickert, Spencer Gore and his close friend James Bolivar Manson with whom he went on painting expeditions and corresponded over many years. He made an important contribution in bringing a new impetus to British painting in the early years of the twentieth century.

[1] Quoted in Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, Milan 2005, vol. I, p.181.

[2] Quoted in ibid., vol. I, p.136.