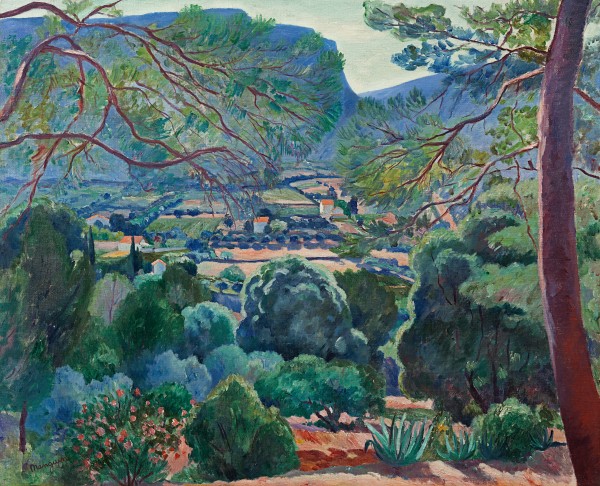

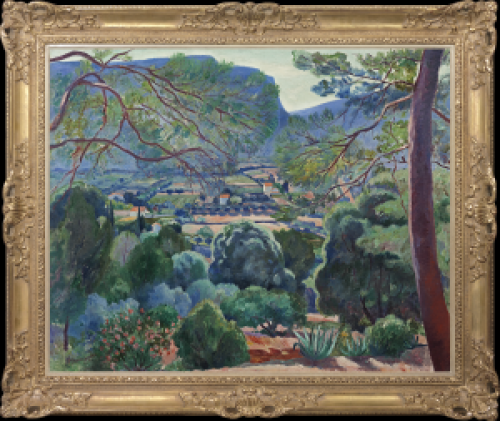

HENRI MANGUIN

Paris 1874 - 1949 St Tropez

Ref: CC 155

Nu sur un canapé

Signed lower left: Manguin

Oil on canvas: 19 ¾ x 24 1/8 in / 50.2 x 61.3 cm

Frame size: 31 x 34 in / 78.7 x 86.4 cm

Painted in Lausanne in 1915

Provenance:

Dr Hans Schuler Collection, Winterthur (acquired from the artist in January 1916);

Kunsthaus, Zurich (bequeathed from the above in 1920)

Galerie Beyeler, Basel

Private collection, Paris, by 1967

Galerie de l’Elysée (Alex Maguy), Paris, no.1299 (as Composition)

Teri and Bernard Solomon Collection, Los Angeles;

their sale, Sotheby Parke Bernet, Los Angeles, 4th February 1975, lot 309

Private collection, USA, by 1980

(Possibly) Ansley Graham, Los Angeles

Michelman Fine Art Inc., New York;

acquired from the above in December 2003 by a private collector, USA

Literature:

Exh. cat., Henri Manguin, Fauve Master (1905-1910), Los Angeles 1974, illus.

Marie-Caroline Sainsaulieu, Henri Manguin Catalogue Raisonné de l’Oeuvre Peint sous la Direction de Lucile et Claude Manguin, Neuchâtel 1980, p.190, no.504, illus.

Henri Manguin was a pupil with Matisse, Marquet, Rouault and Camoin in the studio of Gustave Moreau, a liberal teacher who sensed the ferment of originality in these young men: he told them that he was the bridge over which they would pass. They sprang to notoriety at the 1905 Salon d’Automne, with paintings in which vivid, anti-naturalistic colour is used as a vehicle to express emotion. Perspective, paramount since the Renaissance, was jettisoned in favour of eddying black lines and a pulsating picture plane. The outraged critic Louis Vauxcelles dubbed these artists ‘Fauves’ (wild beasts).

Manguin’s daughter Lucile described her father as ‘homme sensible, cultivé, passionné…aussi habité d’une grande energie’. Charles Terrasse, nephew of his friend Pierre Bonnard, commented: ‘Manguin, c’était une contraste de force quasi agressive et d’affabilité…Il colerait ou riait; il était tout en extreme comme un Fauve généreux’[1]. Reflecting his spirit, this painting is full of a fierce joie de vivre, despite the wartime circumstances under which it was made. At the end of 1914, as the First World War broke out, Manguin relocated his family from Cassis in the South of France to Lausanne in neutral Switzerland. Through his friend, the Swiss painter Félix Vallotton (1865-1925), Manguin had gained several important Swiss patrons and collectors of the French avant-garde, including the ophthalmologist Alfred Hahnloser and his artist wife Hedy. Manguin had stayed with the Hahnlosers at Winterthur in 1910 and was enraptured by the Swiss landscape, exclaiming to Vallotton: ‘Quel sacré pays!’.

Manguin remained in Switzerland throughout the War, exploring the area around Colombier, near Neuchâtel, where he made several pictures. At his home on the Avenue de Rumine in Lausanne, he also painted still lifes of flowers and a number of nudes, using his wife Jeanne-Marie as a model. Nu sur un canapé, 1915, is among the finest of these intimate, sensual works. Jeanne lies on a sofa, the curves of her body depicted in caressing strokes of flesh tones striated with purple and green shadows. She is cocooned in a room of vivid colour, vibrant as the palette of Manguin’s Fauve years. Shadows of red and purple gather in the corner of the room, broadening out to green and yellow in the sunlit area behind Jeanne’s glossy, dark chignon. The furnishings are a riot of complementary colours: orange and purple in the carpet, green and orange in the cushions, red and midnight blue in the tablecloth. Manguin transforms a cluttered, bourgeois interior into the exotic lair of an odalisque.

The nude Jeanne turns away from the viewer, her neat profile simplified and private, her thoughts unknowable. Her body is mirrored by the full-length painting of an uncoiled nude, face-on, hung on the wall above her. Manguin is referencing his own nudes from this period, such as Nu allongée, 1915 (private collection, France)[2], but also the tradition of Old Master nudes, such as Titian’s magisterial Venus of Urbino, 1534 (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence), who is as at ease in her own skin as Manguin’s Jeanne.

Nu sur un canapé stands as part of a long tradition of painting the female nude in French art, from the playful nakedness of Boucher, to the odalisques of Ingres, to Manet’s notorious Olympia, Degas’s domestic nudes, to the joyous, pagan sensuality of Renoir’s nude compositions, which Manguin much admired. Nudes also formed an important part of the work of Manguin’s Fauve colleagues, including his lifelong friend Henri Matisse. Matisse’s Lorette allongée sur lit rose, 1916 (Stavros D Niarchos Collection) has a similar interest in depicting a simplified nude in a setting of vibrant pattern. Manguin’s Nu sur un canapé also finds echoes in the rich interiors of Matisse’s overtly Orientalising, semi-nude odalisque paintings of the 1920s, such as the Reclining odalisque, 1926 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

Manguin’s patrons the Hahnlosers were at the hub of a circle of art connoisseurs that gathered at their Villa Flora in Winterthur; today the villa and their collection is part of the Kunst Museum Winterthur. The Zurich collector Dr Hans Schuler, part of the Hahnlosers’ network of art enthusiasts, acquired Nu sur un canapé directly from Manguin in January 1916.

HENRI MANGUIN

Paris 1874 – 1949 St Tropez

Henri Manguin was born in Paris in 1874. In 1894 he entered the studio of Gustave Moreau at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, a fellow pupil of Matisse, Marquet, Rouault, Valtat and Camoin, who remained lifelong friends. In 1899 he married his muse and model Jeanne Carette and in 1902 exhibited for the first time at the Salon des Indépendents. Manguin first discovered the South of France in 1904, when he was invited to Saint-Tropez by Paul Signac, with whom he shared a love of fast cars. The dazzling Mediterranean light had a profound effect on Manguin’s work. Manguin and his friends showed paintings with emotionally-charged, anti-naturalistic colour and shifting perspective at the 1905 Salon d’Automne, provoking the critic Louis Vauxcelles to dub them ‘fauves’ (wild beasts). The following year Ambroise Vollard bought 150 of Manguin’s works.

Manguin depicted nudes, landscapes, interior scenes and still lifes in a direct, painterly style, although the palette of his later work is softer and more naturalistic than that of his Fauve period. From the 1920s, like Matisse, he divided his time between Neuilly-sur-Seine to the west of Paris and the South of France, renting, then buying, a house called l’Oustalet at Saint-Tropez. Manguin also made painting trips to Normandy, Brittany and other parts of France and to Switzerland, where he gained important patrons through his friendship with Félix Vallottan. Manguin died at Saint-Tropez in 1949. In 1950 the Salon des Indépendents organized a major retrospective of his work.

The work of Henri Manguin is represented in the Musée d’Orsay, Paris; the Hermitage, St Petersburg; the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and the Art Institute of Chicago.

[1] Lucile Manguin, ‘Henri Manguin, mon père’, in Paris, Musée Marmottan, Henri Manguin 1874-1949, 19th October 1988-8th January 1989, p.19.

[2] Sainsaulieu, op. cit., p.190, no.503.