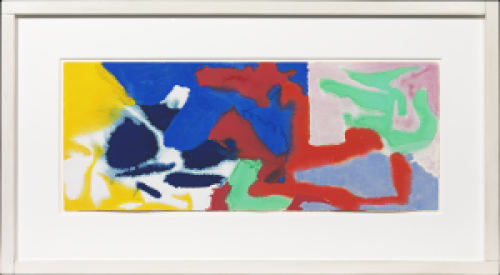

BEN NICHOLSON OM

Denham 1894 - 1982 London

Ref: CC 166

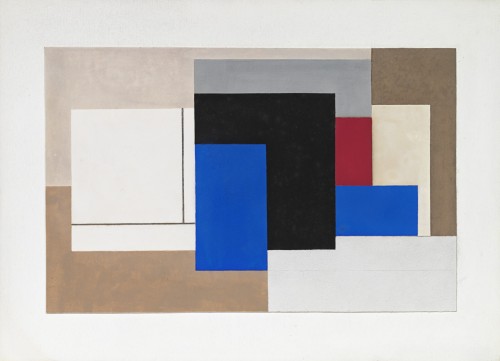

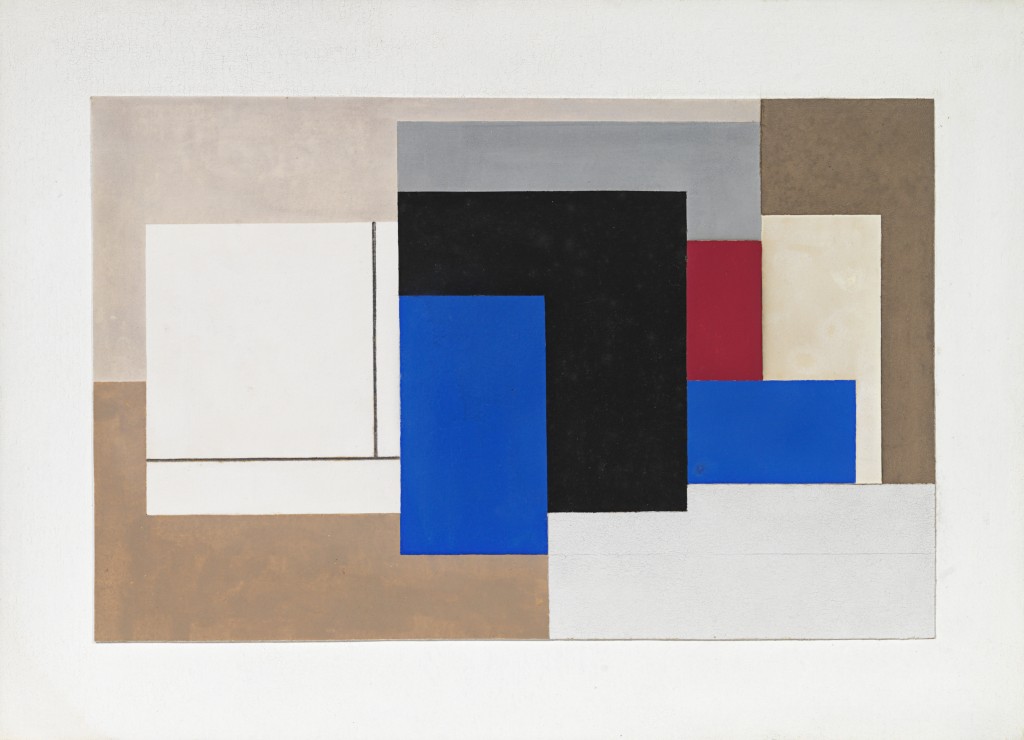

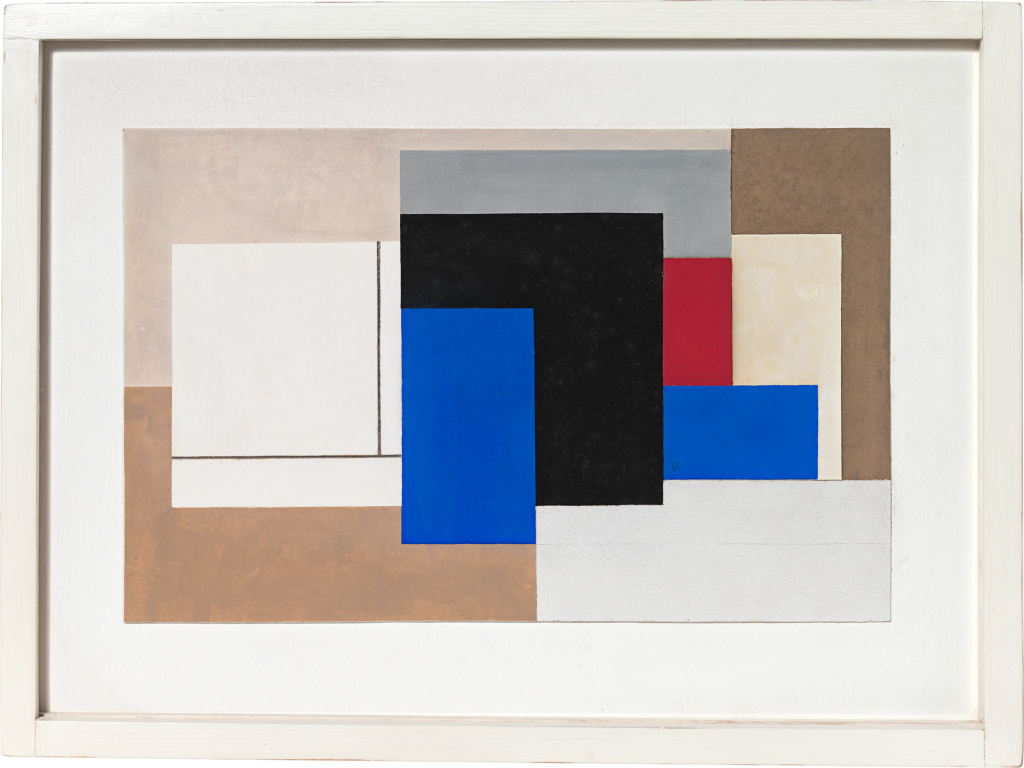

1942 (painting)

Signed, dated and inscribed on the reverse: Ben Nicholson / 1942 Signed again and inscribed with the artist’s address: Nicholson /

Chy an Kerris / Headland Road / Carbis Bay / Cornwall

Gouache and pencil on the artist’s board with relief, laid on the artist’s prepared board: 9 x 12 ½ in / 22.9 x 31.8 cm

Frame size: 9 ¾ x 13 ⅛ in / 24.8 x 33.3 cm

In its original asymmetrical frame

Provenance:

Marcus Brumwell CBE FRSA (1901-1983), acquired directly from the artist and then by descent

To be included in the forthcoming catalogue raisonné of the paintings and reliefs of Ben Nicholson currently being prepared by Dr Rachel Smith and Dr Lee Beard.

In early July 1942 Ben Nicholson took out a seven-year lease on Chy-an-Kerris in Carbis Bay, the address inscribed in the artist’s hand on the verso of 1942 (painting). Nicholson had moved to Cornwall with Barbara Hepworth and their children three years earlier. Perhaps sensing a potential ebbing away of the progressive ambitions and achievements of his peers in pre-war London and the wider network of contemporary artists and writers he had become part of across Europe, Nicholson entered a period of consolidation regarding his own modernist position and practice. In the spring of 1942, a selection of his abstract paintings and reliefs were included in the ‘New Movements in Art’ exhibition at the London Museum, where they were displayed alongside works by, among others, Piet Mondrian, Henry Moore, Hans Erni, and Hepworth. In many ways the exhibition marked a reassertion of the constructive and non-figurative standards set out through Circle five years earlier, and it was noted in the catalogue that the vast majority of artworks included had been executed in England in the intervening years.

During the war years, Nicholson endeavoured to promote his modernist and constructive ideas through a range of publications. This was something that he worked on closely with the original owner of 1942 (painting), Marcus Brumwell, due to the latter’s role as arts editor for the World Review. Nicholson had first met Brumwell in the 1920s at the East Dulwich Tennis Club, and they would soon forge a close friendship, with Brumwell becoming an important patron and supporter of the artist’s career. Through his position as executive at Stuart Advertising Agency he secured a number of commercial commissions for Nicholson, including poster designs for Imperial Airways and Shell. By 1942 Nicholson was working alongside Brumwell as a commissioning editor for World Review, a role – as the vast correspondence between them attests – to which he was fully committed. Writing to Brumwell regarding the early development of the magazine, Nicholson was adamant that, at a time of social and political uncertainty, recent developments in art and architecture should have a prominent position alongside contemporary thinkers from a wide range of disciplines.

… one can say that along with the liberation of men, of women – of children – there is also the liberation of form and of colour (abstract art) and surely there are through this looking glass obvious parallels to these liberations in contemporary physics, psychology, music, poetry and religion today?

[Correspondence with Marcus Brumwell, 20th February 1941][i]

Central to Nicholson’s own artistic practice during the period was the focused development and refinement of form, line, and colour, in his paintings. At times making slight adjustments to compositions within a series or working on a small scale in gouache to explore a new formal arrangement – of which 1942 (painting) is an excellent example – Nicholson strove to find the right ‘pitch’ by which his idea could be most directly achieved. As Nicholson would explain at that time, although such works appeared to have no obvious ‘subject-matter’, he only valued “purely abstract painting” when it was arrived at “by working for a long time from something actual”.[ii]

In painting a ‘still-life’ one takes the simple every-day forms of a bottle – mug – jug – plate on table as the basis for the expression of an idea: the forms are not entirely free though they are free to the extent that each object can be seen from as many viewpoints as you wish at one and the same time, but the colours are free: bottle-colour for plate, plate-colour for table, or just as you wish, and working in this way you have in time not a still-life of objects but an equivalent of something much more like a deer passing through a winter forest, over foothills and mountains, through sunlight and shadows in Arizona, Cornwall or Provence, and so, inevitably, you eventually discard altogether the forms of even the most simplest objects as a basis, and work out your idea, not only in free colour, but also in free form.

(Ben Nicholson, ‘Notes on Abstract Art’, 1941)[iii]

With Nicholson’s explanation of the formative significance of the still life in mind it is revealing to compare 1942 (painting) with Gouache 1938-42 in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, a painting of similar dimensions. Whereas such juxtapositions illustrate the methodical distillation of form, and unfolding of compositional ideas in his oeuvre, as he explained in a letter to Herbert Read, this was a process that he would sometimes progress by working across different materials and techniques. In 1942 this was evident in his renewed interest in working with collage. Earlier in the year he had met the Dada artist Kurt Schwitters, who was at the time living in London. Nicholson was very likely already familiar with Schwitters’ ‘Merz’ collages, as both had been participants in Paris centred Abstraction-Creation group in the previous decade. Nonetheless their meeting in 1942 appears to have encouraged Nicholson to revisit the medium, as is evident in 1942 (bus ticket), which he would give as a gift to Schwitters. Comparable in its construction of planar forms and line to 1942 (painting), Nicholson explained to Read how working in collage could help to inform his paintings,

… one might use complicated gradations in painting a square section + if instead you cut out a square piece of plain paper + stick it on you suddenly have something simple + direct which later when you return to ptg [painting] gives you a new simplicity + directness.

(Letter to Herbert Read, 21st August [1941])[iv]

This is a ‘simplicity and directness’ that is clearly found in 1942 (paining), an artwork indicative of Nicholson’s unwavering commitment to the potential of abstract art and its centrality to the wider application of modernist principles throughout the 20th century.

Dr Lee Beard, 2024

[i] Tate Gallery Archive 8717.1.3.3.

[ii] Letter to Jake Nicholson, 2nd January 1940, reproduced in Lee Beard (ed), Ben Nicholson: Writings and Ideas, Lund Humphries, London, 2019, p.42.

[iii] Ben Nicholson, ‘Notes on ‘Abstract’ Art’, Horizon, vol.4, no.22, October 1941, p.274.

[iv] Tate Gallery Archive 8717.1.3.49