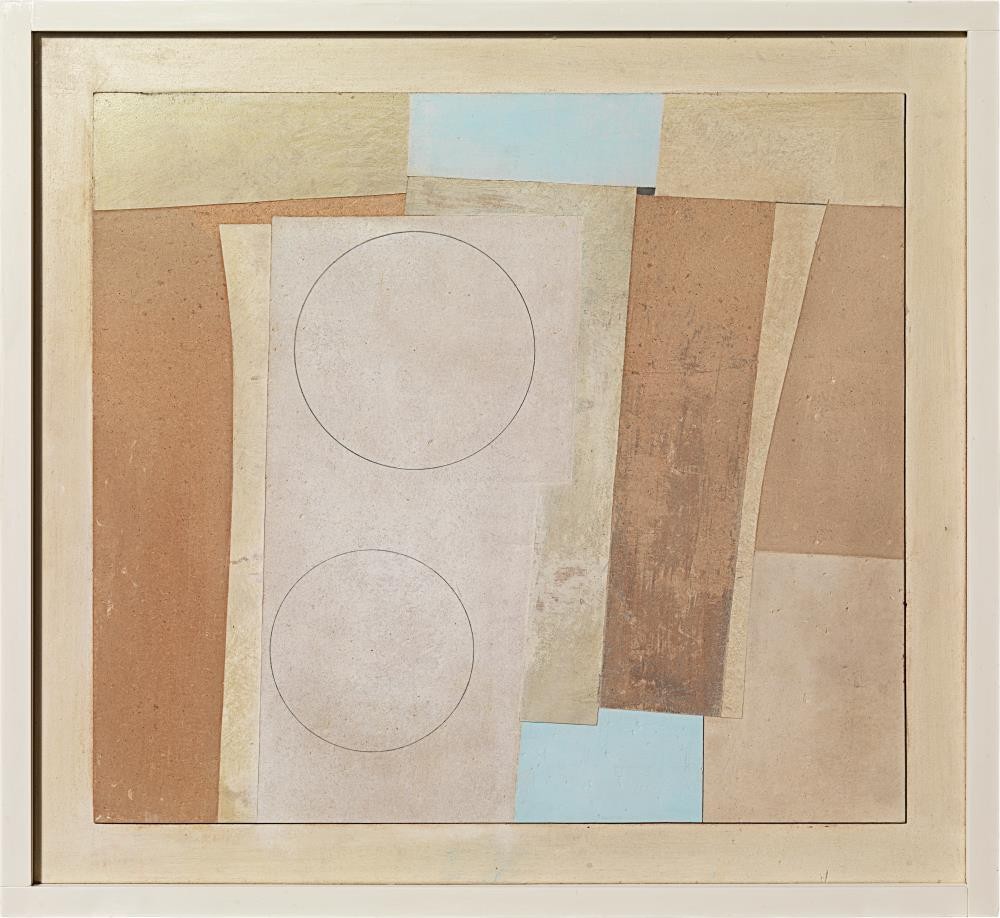

Ben Nicholson

Nov 59 (landscape with monolith)

Oil and pencil on carved board relief: 21.5 x 23.5 (in) / 54.6 x 59.7 (cm)

Signed, dated and inscribed on the reverse: Ben Nicholson / Nov 59 / (landscape with monolith)

This artwork is for sale.

Please contact us on: +44 (0)20 7493 3939.

Email us

BEN NICHOLSON OM

Denham 1894 - 1982 London

Ref: CB 187

Nov 59 (landscape with monolith)

Signed, dated and inscribed on the reverse:

Ben Nicholson / Nov 59 / (landscape with monolith)

Oil and pencil on carved board, relief, on the artist’s prepared board: 21 ½ x 23 ½ in / 54.6 x 59.7 cm

Frame size: 23 ¼ x 25 in / 59.1 x 63.5 cm

In a painted tenoned corner frame

Provenance:

Gimpel Fils, London;

private collection, acquired from the above in 1963

Redfern Gallery, London;

Neville Burston, acquired from the above 7th February 1966

Andre Emmerich Gallery, New York

Sotheby’s New York, 19th November 1981, lot 38;

Eph and Shirley Diamond, Canada

Exhibited:

London, Gimpel Fils, Ben Nicholson: Works 1956-60, July 1960, no.16

Dallas, Museum of Fine Arts, Ben Nicholson: Retrospective Exhibition, April-May 1964, no.55

London, Redfern Gallery, Summer Exhibition, 21st June – 3rd September 1966, no.335

To be included in the forthcoming catalogue raisonné of the paintings and reliefs of Ben Nicholson currently being prepared by Dr Rachel Smith and Dr Lee Beard.

In the summer of 1958 Ben Nicholson moved into his new home and studio, Casa Vecchio, in Ronca sopra Ascona, Switzerland. It was here that he completed Nov 59 (landscape with monolith). On arriving in the municipality earlier the previous year, the artist had noted that the view was ‘so beautiful that’ he could ‘hardly believe it.’[1] Remarking that there was a ‘fine sculptural block of mountains’ visible across Lake Maggiore, this environment appears to have found its way into the compositional structure of Nov 59 (landscape with monolith). As the artist would explain in a contemporaneous interview in The Times,

‘The landscape is superb, especially in winter and when seen from the changing levels of the mountain side — the persistent sunlight, the bare trees seen against a translucent lake, the hard, rounded forms of the snow topped mountains, and perhaps with a late evening moon rising beyond in a pale, cerulean sky — is entirely magical and with the kind of visual poetry which I would like to find in my painting.’[2]

Nicholson felt that when approaching a painting ‘it should be as impossible to separate form from colour or colour from form as it is to separate wood from wood-colour or stone-colour from stone.’[3] This is a quality he clearly achieves in Nov 59 (landscape with monolith), where the flat areas of blue, redolent of a boundless sky, are offset against the scored and pitted surface of Alpine granite grey. As with many of Nicholson’s finest artworks from this period, colour plays an essential part in evoking a potent sense of nature and human experience, in which the passing of time is firmly embedded in the materiality of the artwork.

The reliefs and paintings that Nicholson completed in Switzerland during the decade marked a successful consolidation of many factors that had preoccupied him throughout his career. A significant aspect of this was his engagement once again with a more explicitly abstract focus within his work, particularly evident in his return to the carved relief. During the period Nicholson had remarked that working in relief brought a different dimension to his artistic practice. Noting that whereas canvas is stretched ‘most easily into a conventional form,’ a ‘board can be carved into any form,’ and as such had the possibility to become ‘an object – not only an everyday object but an object (“idea”) beyond […] temporary existence.’[4]

Nicholson would have worked on Nov 59 (landscape with monolith) flat upon a tabletop, using a variety of chisels and razor blades. Not only were the blades used to remove areas of applied paint to reveal underlying colour or exposed board – creating a timeworn poetic quality – but the density of the support enabled Nicholson to use the blades to create precise edges that delineated the subtle differences of depth whilst holding the tonal and textural areas of colour in place. As Nicholson would explain to his friend Adrian Stokes, ‘I like the relief as a means of expression as it gives me so simply the structure that I must have & then one can pursue one’s idea on this basic building rather like a tree in spring grows its leaves.’[5]

The carved reliefs from this period were shaped by Nicholson’s desire to bring together, and hold within an artwork, traces of an experience or an idea. These were qualities that Nicholson had felt permeated the ancient sites and historical buildings that he visited across many European countries. On seeing the prehistoric standing stones at Carnac in Brittany, he recalled that he had experienced a ‘tremendous feeling’ of ‘events having happened in the past.’[6] This was a sensation and quality that he also found among the ancient ruins and rock-strewn landscapes of Delos, Olympia, and Delphi, sites which he a had spent time drawing with complete absorption during his first visit to Greece in the spring prior to completing Nov 59 (landscape with monolith). Whilst Nicholson was adamant that the titles of his artworks were not to be read as suggestive of specific subject matter, the present work can perhaps be seen as a successful synthesis, an equivalent to the many forms and landscapes encountered by the artist during his travels across Europe at the height of his career.

Dr Lee Beard (2024), author of Ben Nicholson: Writings and Ideas (Lund Humphries, 2019).

[1] Letter to Winifred Nicholson, Casa Ticinella, Ronco/Ascona, Ticino, 5th April [1958].

[2] ‘Mr Ben Nicholson answers some questions about his work and view’, The Times, 12th November 1959.

[3] Ben Nicholson, ‘Notes in a Tate Gallery Catalogue’, Ben Nicholson: a retrospective exhibition, Tate Gallery, 1955.

[4] Typewritten copy of letter to Charles Harrison, 30th November 1966. Tate Galley Archive [TGA]

[5] Letter to Adrian Stokes, 6th January 1963, TGA.

[6] Letter to Herbert Read, 30th October 1963, TGA.